Principle 3 – Ecological Balance

Restoration projects should aim for and achieve outcomes that are representative of the historical ecology of the wetlands before development, take into account the current constraints and adjacent human uses, and maximize the most valuable long-term benefits for plants and animals.

Description:

A wetland restoration project needs to consider the historical ecology of the area. Given the extensive development in southern California, it is not possible to restore conditions to any point in history exactly, particularly pre-human impact. However, considering historical ecology can provide useful information such as types of habitats, plants, and animals that previously existed on the site, and how the system functioned without major stressors; this information can help set restoration goals and conservation metrics. Goals should be set to achieve a system that is self-sustaining and needs minimal human intervention. There needs to be a balance in the restoration planning between considerations of what the site looked like and how it functioned before human impacts and what the current conditions and constraints are. Southern California wetlands are currently constrained by loss of habitat, poor water quality, fill, flood control concerns, and nearby development such as roadways, homes, and industry, among other constraints. Further, wetland ecosystems are not static; they are dynamic and ever-changing and adaptive management is necessary component of a successful restoration.

Dr. Christina Eisenberg, ecologist and Chief Scientist with the Earthwatch Institute says (in her first book The Wolf’s Tooth), “ecological restoration is the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed. However, in any act of restoration it is never possible to return exactly to what once was; one can only move forward. This means recovering a natural range of variation of composition, energy flow, and change, bringing a system back to its historical trajectory. Historical trajectories are only that, since we cannot predict the future. We can only work with what we think will optimize adaptability, resilience and productivity. The past is not a blueprint for the future, but we can assess these historical trajectories and think about management for future change. This calls for restoring to landscapes as much of their functional diversity as possible, which often means including top predators. Restored systems should ideally be self-sustaining and resilient, exchanging energy with interconnected ecosystems and migratory species. The system should contain all functional groups (plants, herbivores, predators) and should support reproducing populations of the species necessary for their continued development and resilience…”

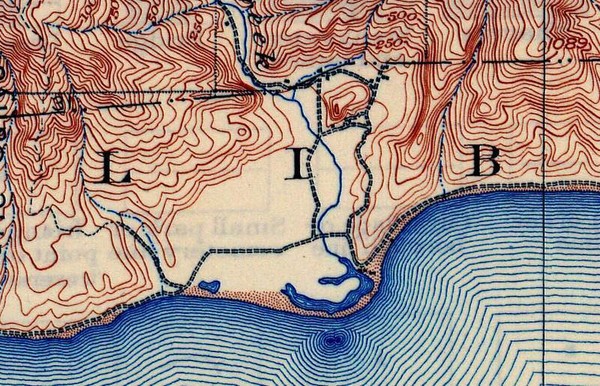

The following images show Malibu Lagoon at different points in time, showcasing the historical condition, before major development, and how current constraints (Pacific Coast Highway, residential development at the Colony, commercial development at Cross Creek Shopping Plaza, golf course) prevent or complicate restoration to the pre-development condition. However, a balanced restoration, considering those constraints, took place in 2012 to increase circulation and improve hydrology, among other goals.

Malibu Lagoon in 1903, before major development. Note the westward extent of the Lagoon.

Malibu Lagoon in the 1970s. Note the reduced size of the Lagoon, the presence of Pacific Coast Highway (PCH), the houses at the Colony, and the baseball fields in the wetlands.

Malibu Lagoon in 2009. Post-1983 restoration by California State Parks, which removed the baseball fields and created three tidal channels in the estuary.

Malibu Lagoon December, 2014. Post 2012-2013 restoration by Santa Monica Bay Restoration Foundation and CA State Parks, which removed sediment and re-contoured western channels to improve water flow and circulation. Photo courtesy of Lighthawk and The Bay Foundation.