Principle 1 – Functional Integrity

Restoration projects should bring back the natural processes and functions of healthy wetlands, using broadly accepted scientific evidence of historic, present, and potential conditions to set ambitious and achievable restoration goals and quantifiable measures of success.

Description:

Restoration efforts should use scientific evidence as the backbone of efforts to restore wetlands to their natural and healthy functions; in this state, wetlands are able to maintain their resiliency even during periods of stress and thrive in their natural environment. Wetland functions are the processes that occur in wetlands and the services that they provide, including carbon sequestration, groundwater recharge and habitat provisions. Wetlands do not all provide the same functions, however, and there is no one way to define a “healthy” wetland. Wetland functions vary based on geographic locations and their positions in the watershed. As such, it is important to evaluate the functions that your wetland of interest has historically provided and which ones it is currently lacking, and then decide on restoration efforts from that point of departure.

Restoration efforts are also generally more fruitful when they not only imagine large-scale restoration ideals, but also connect these objectives with quantifiable values. For instance, restoration practitioners may want to consider acres of restored habitat, the species richness of native plants and calculations of water quality. These measures of success should connect to the objectives of the restoration effort. A wetland project might appear to be a success because of an increase in the amount of vegetation, but if the restoration group overlooks the biodiversity of the vegetation as an indicator, the effort might in fact be a failure. Defining numerical values reduces uncertainty, provides firmer goals and also connects the effort to the public more easily. Quantifications should also take into account potential upcoming changes in the environment and social landscape.

This image shows scientific monitoring of marine life in the Ballona east channel to examine current conditions to guide future restoration goals. Photo by Lisa Fimiani.

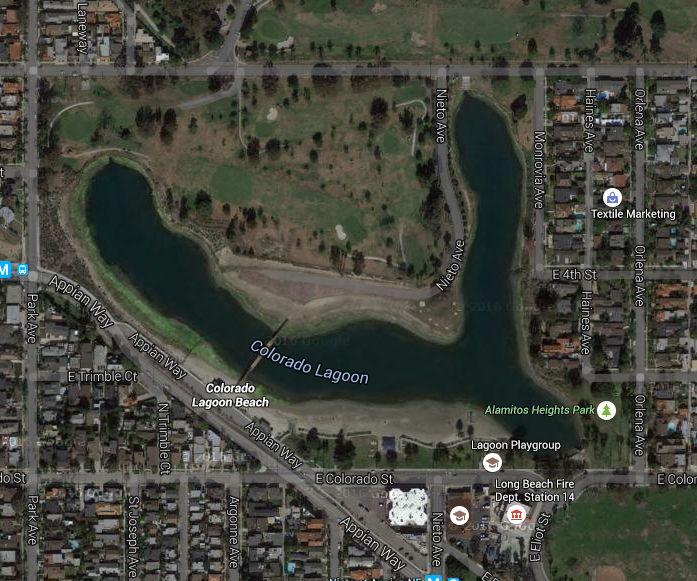

This photo from 1954 shows a pre-restoration state of the lagoon when the waterbody played a significant role in local recreation, but was struggling with water quality concerns (Source: Friends of Colorado Lagoon).

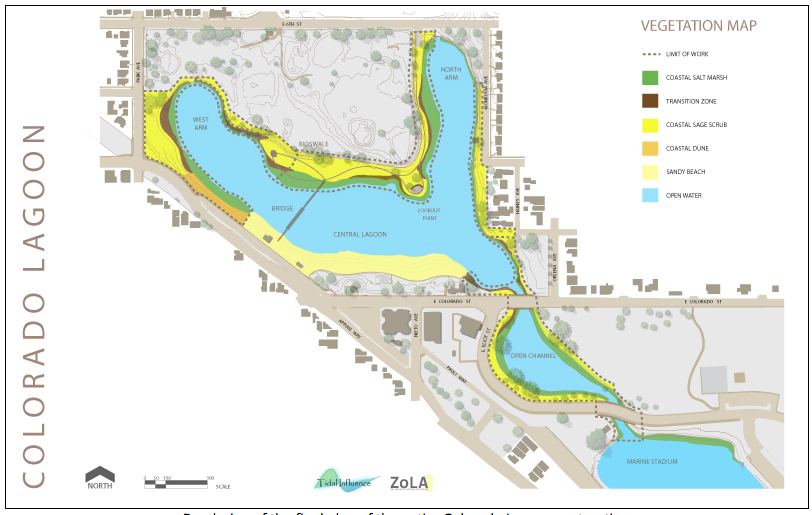

This July 2016 photo shows the present day conditions with restoration efforts underway — such as through the planting of thousands of native species — but not complete.

This rendering illustrates the hopeful appearance of the lagoon at the completion of current restoration efforts when there will most notably be full tidal flushing (source: Friends of Colorado Lagoon).

Reference:

Middleton, Beth A., and Nicholas J. Souter. “Functional Integrity of Freshwater Forested Wetlands, Hydrologic Alteration, and Climate Change.” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability Ecosyst Health Sustain 2.1 (2016): n. pag. Web.

“Principles of Wetland Restoration.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, n.d. Web. 06 June 2016.

“Restoration, Creation, and Recovery of Wetlands Wetland Functions, Values, and Assessment.” Wetland Functions, Values, and Assessment. N.p., n.d. Web. 06 June 2016.